(published in JigsawZen.com in 2006)

When I was a kid we used to go on holidays to a place by the seashore near Buenos Aires. My parents had to stuff suitcases, sunshades and what have you into the car trunk plus four kids (me and my bros) for a five hour drive to the seashore. A good way to keep the over crowded car more or less in order during those long hours under the blazing Sun was to buy us a few comics before leaving. That way, we would each read our own magazine for most of the trip instead of fighting and being a pain in the ass.

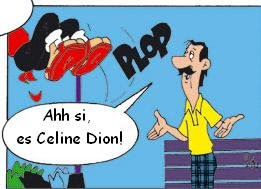

Our favorite one was ‘Condorito’, a Chilean comic with a curious character based on a condor. He was kinda like Donald Duck now that I think of it. Anyway, this ‘Condorito’ fella was a rascal and always had some ingenious thing to say in the last frame. One thing that’s characteristic in this comic is that there’s always someone who sort of faints in reaction to his last remark. You can usually see a pair of legs flying in the air as the character falls back and big fat letters with the word ‘PLOP!’

Koans remind me of ‘Condorito’…

Koan is a Japanese word (Chinese: ‘Gong-an’) which means ‘public case’. It’s actually a case study -or an example- that is used to show Zen students some obscure aspect of Zen. Koans are usually short stories or dialogues between two monks in which one of them gets enlightened in the end. So it’s kinda like a comic: there’s a short dialogue between two characters with a clever ending punch. This ending punch is often what causes the student monk to finally ‘get it’ with a thundering flash. I can almost visualize a shaven dude in robes falling over backwards and the word ‘PLOP’ in fat red letters.

Ah… Those are the profound thoughts that go on in my mind as I ponder the unfathomable depths of Zen wisdom…

Anyway, now that I’ve convinced you that I take these koan things very seriously, let me tell you a bit about them. The idea, at least as far as I can see it, is that an example is much more educational than an explanatory discourse. This is even more evident when what you’re trying to explain is ‘beyond words’ (see an article I wrote about that here). Although there’s quite a bit of debate as to how these stories are supposed to be used (and tradition dictates fairly strict rules for their use and discussion) I will go ahead and just pour out my own personal take on them.

Personally, I think koans are great. I take them as poems. Or rather, like concise and poetic illustrations of Zen logic. Even if their rational interpretation is close to an absolute waste of time, when I reflect upon them there is usually some sort of wordless understanding that slowly-timidly starts to surface. Don’t get me wrong! Claiming I actually understand them is a bit more blasphemous than what I am willing to be on this webpage. I can be sent to the pyre for that! I’ll tell you this though: after some years of reading koans and letting them float in my mind, that which initially sounded like absurd gibberish starts making some sense; at least as a soft and elusive whisper.

And even if Nipponese tradition seems to get all worked up about how these things should be discussed under the strict rules of dokusan, I prefer to try to put those whispers into words (so help me God).

Check out this koan from the Mumon-kan:

NANSEN’S ORDINARY MIND

Joshu asked Nansen, “What is the Way?” Nansen answered, “Your ordinary mind.”

Joshu again asked, “Can it be studied?” Nansen replied, “The more you pursue, the more does it slip away.”

Joshu asked once again, “How can you know it is the Way?” Nansen responded, “The Way does not belong to ‘knowing’, nor does it belong to ‘not knowing’. Knowing is an illusion. Not knowing is outside the field of discrimination. When you get to this Way without doubt, you are free like the vastness of space, an unfathomable void. How can you explain it by affirmation or negation?”

Upon hearing this, Joshu suddenly understood (PLOP!).

Mumon's Comment:

The question Joshu asked Nansen was dissolved with one stroke. After being enlightened, Joshu should further pursue these words for thirty years to exhaust their meaning.

A hundred flowers in Spring, the moon in Autumn,

The cool wind in Summer and the white snow in Winter.

If your mind is not clouded with things,

You are happy at any time.

And now comes my blasphemy:

What Joshu asks is, in some way, something that we all have on our minds. Yeah, I realize you don’t go around looking like Little Grasshopper asking monks what the ‘Way’ is. In fact, even if this idea might abide in some dark crevice of your mind, it is quite probable that you’ve never uttered this idea in the form of a direct question. What Joshu is asking is simply this: What is happiness? What is freedom? How can I live a happy life? Yes, I realize Joshu has phrased his question quite a bit differently but the words that are used depend on the values and notions of the culture they come from. In Joshu’s days, ‘Way’ was the meaning of the word ‘Tao’. Joshu was asking: What is the Tao? Some translations have Joshu ask: What is the Buddha? But it’s all the same thing. Joshu is asking for some specifications on what is the meaning of harmonizing with the Tao; what are the coordinates of our true nature (referred to as the Buddha Nature), what is the spontaneous healthy state of mind that brings around happiness and freedom.

Many people believe that happiness and freedom are things that we’re supposed to set out for, things that we have to acquire by doing stuff or changing our surroundings. Say, like having a bunch of money or being really famous. Others believe that these may be acquired by changing something within ourselves, like attaining certain states of mind. When ancient translations offer words like Buddha Mind or some other cryptic word for this situation, we seem to have a tendency to imagine super wacky states of mind. I used to think of the Buddha Mind as some detached, serene and all-knowing coolness. Wouldn’t it be great? Ah, all is falling apart and yet I’m just chill… Your round-the-corner-bookstore is bound to be packed with books that show you how to get to these ‘higher states of consciousness’ and propose methods and spiritual practices that serve as tickets to some ‘Prozac meets Xanax’ paradise.

But Nansen answers: ‘Hey, come down from the clouds! Stop imagining wacky stuff! Your ordinary mind, your stupid little confused mind is ALREADY IT. Anything else is just your imagination. Your little mind that thinks of koans that end with a PLOP is already the Tao. That is the Buddha Mind. Buddha Mind is not something special; it’s in fact quite ordinary.

But Joshu is no fool. I have this feeling that he knew exactly what Nansen was going to answer. He already knew about the ordinary mind and yet there were some things that didn’t quite fit. So following these lines, he shoots Nansen again: ‘How can it be studied (or developed)?’ That’s another thing that we have a tendency to do. We need to enhance, maintain or induce that which we believe to be good or desirable. If my ordinary mind is the Buddha Mind or the Tao then, what can I do to always have this mind? How can I keep it or make it even better? How can I follow this path to the ordinary mind?

But Nansen replies with words that are difficult to digest and truly hard to understand: ‘The more you pursue, the more does it slip away’. Your stupid, crappy little mind is already the Tao. Whatever you do to try to seize it, enhance it or improve it will just mess things up. It’s like stirring murky water to make it clear.

Many Zen teachers seem to have a standard answer for these things: ‘You just do zazen and it will all be settled.’ I find that a bit annoying. It’s like when you were a kid and someone would tell you: ‘You’ll understand it when you grow up’. However, and I am not a Zen Teacher mind you, I have to grant that while doing zazen all the stuff that’s going on in our minds becomes a bit more evident; it shows just a bit more clearly. In order not to sound like some pretentious Zen Master know-it-all, I’ll just share a bit of what happens to me. When I sit in zazen, the ordinary mind is there, flowing along in front of my attention. There are no obstructions. It just flows effortlessly and the usual parade of nonsense just goes by. Homer whacking Bart on the head… You know? The usual stuff. But then I get this itch, this anxiety to try and explain it, to try to control it or to change it. But the paradox is that when I try to seize it -to explain it- it’s like if I had to step out of my ‘mind’ to be able to rationalize it. It’s like moving away from the picture to see it in full scale. Anyway, when I do this, the flow is interrupted and the spontaneity is lost.

But our hero Joshu had already seen all this coming and had his third question ready and waiting. I imagine his reasoning was something like this: if my ordinary mind is already the Tao and there’s nothing I’m supposed to do to study it, then I just have to sit on my bum and do nothing! How can this be the Way? Isn’t this something like the Emperor’s New Clothes? What’s the difference then between just hanging around doing nothing and practicing the True Dharma preached the Buddhas of all times? If I just go about my business with my everyday state of mind, how can I be sure this is the True Way?

And this is when I should shut my big fat mouth.

Nansen’s reply is wonderful, concise and enlightening. How could I put my words on top of his? There’s an expression used in Zen teachings that goes something like: it would be like throwing buckets of water into the ocean. By trying to explain Nansen’s words, in fact, I would be throwing mud into the water to make it clear…

So let’s begin then. Here goes the first handful of mud…

Nansen replies Joshu by first tackling the issue of ‘knowing’ and ‘not knowing’. In this case, ‘knowing’ is meant as rational knowledge. How can I know it is the Way? What Joshu wants is some evidence, some convincing argument that holds its own water. He wants to be able to discuss this with his friends over dinner and tell them: ‘Hey, check this out: the Way is the Ordinary Mind. Breakthrough scientific research has proven that the limbic system is the blah, blah, blah.’ But these are just illusions. They are just more dopey thoughts parading in the sea of nonsense that goes on in our minds all the time. This discrimination is just a process of deconstructing experience into thought units (which we call ‘things’) and relate them thru a set of rules (which we call ‘logic’). But in the end, they are not reality; they are nothing but abstractions (Buddhism refers to these as ‘imaginations’.)

‘Not knowing’ is just the other side of the same coin. It is the things that we believe exist even if we are not aware of them or cannot explain them. It’s just the stuff that we are not discriminating, deconstructing and relating. How could this be relevant? It’s ‘outside the field of discrimination.’

And yet Nansen talks about getting to the path with no doubt. Blind faith, you might say… But it’s not quite that. Nansen means something more like intuition. The problem is that we have an idea of intuition that might be a bit different than what Nansen is talking about. We tend to believe that intuition is kinda like a hunch, like a funny feeling in the stomach. But we don’t usually think of intuition as something very precise or reliable. Anyway, Nansen’s intuition is more of a pre-verbal knowledge; something that we know of even if we haven’t yet put it into words. Getting to the Way without doubt is like recognizing your childhood neighborhood. It’s like looking someone in the eye and knowing that the words being uttered are honest. It’s like ducking when the blow approaches. You need no confirmation, no argument and no explanation. You know it before you ‘know it’; before you give it a name and discriminate it (understand it as something separate) from other stuff. OK?

Ah! But if you were Joshu you would have a fourth question welling up, wouldn’t you? What does all this have to do with happiness?

Even if Mumon gives a hint of this in his comment, at the same time he warns us: Nansen’s words could be dwelt upon for thirty years (a lifetime) before exhausting their meaning. Only then you’ll go PLOP. Won’t you?

When I was a kid we used to go on holidays to a place by the seashore near Buenos Aires. My parents had to stuff suitcases, sunshades and what have you into the car trunk plus four kids (me and my bros) for a five hour drive to the seashore. A good way to keep the over crowded car more or less in order during those long hours under the blazing Sun was to buy us a few comics before leaving. That way, we would each read our own magazine for most of the trip instead of fighting and being a pain in the ass.

Our favorite one was ‘Condorito’, a Chilean comic with a curious character based on a condor. He was kinda like Donald Duck now that I think of it. Anyway, this ‘Condorito’ fella was a rascal and always had some ingenious thing to say in the last frame. One thing that’s characteristic in this comic is that there’s always someone who sort of faints in reaction to his last remark. You can usually see a pair of legs flying in the air as the character falls back and big fat letters with the word ‘PLOP!’

Koans remind me of ‘Condorito’…

Koan is a Japanese word (Chinese: ‘Gong-an’) which means ‘public case’. It’s actually a case study -or an example- that is used to show Zen students some obscure aspect of Zen. Koans are usually short stories or dialogues between two monks in which one of them gets enlightened in the end. So it’s kinda like a comic: there’s a short dialogue between two characters with a clever ending punch. This ending punch is often what causes the student monk to finally ‘get it’ with a thundering flash. I can almost visualize a shaven dude in robes falling over backwards and the word ‘PLOP’ in fat red letters.

Ah… Those are the profound thoughts that go on in my mind as I ponder the unfathomable depths of Zen wisdom…

Anyway, now that I’ve convinced you that I take these koan things very seriously, let me tell you a bit about them. The idea, at least as far as I can see it, is that an example is much more educational than an explanatory discourse. This is even more evident when what you’re trying to explain is ‘beyond words’ (see an article I wrote about that here). Although there’s quite a bit of debate as to how these stories are supposed to be used (and tradition dictates fairly strict rules for their use and discussion) I will go ahead and just pour out my own personal take on them.

Personally, I think koans are great. I take them as poems. Or rather, like concise and poetic illustrations of Zen logic. Even if their rational interpretation is close to an absolute waste of time, when I reflect upon them there is usually some sort of wordless understanding that slowly-timidly starts to surface. Don’t get me wrong! Claiming I actually understand them is a bit more blasphemous than what I am willing to be on this webpage. I can be sent to the pyre for that! I’ll tell you this though: after some years of reading koans and letting them float in my mind, that which initially sounded like absurd gibberish starts making some sense; at least as a soft and elusive whisper.

And even if Nipponese tradition seems to get all worked up about how these things should be discussed under the strict rules of dokusan, I prefer to try to put those whispers into words (so help me God).

Check out this koan from the Mumon-kan:

NANSEN’S ORDINARY MIND

Joshu asked Nansen, “What is the Way?” Nansen answered, “Your ordinary mind.”

Joshu again asked, “Can it be studied?” Nansen replied, “The more you pursue, the more does it slip away.”

Joshu asked once again, “How can you know it is the Way?” Nansen responded, “The Way does not belong to ‘knowing’, nor does it belong to ‘not knowing’. Knowing is an illusion. Not knowing is outside the field of discrimination. When you get to this Way without doubt, you are free like the vastness of space, an unfathomable void. How can you explain it by affirmation or negation?”

Upon hearing this, Joshu suddenly understood (PLOP!).

Mumon's Comment:

The question Joshu asked Nansen was dissolved with one stroke. After being enlightened, Joshu should further pursue these words for thirty years to exhaust their meaning.

A hundred flowers in Spring, the moon in Autumn,

The cool wind in Summer and the white snow in Winter.

If your mind is not clouded with things,

You are happy at any time.

And now comes my blasphemy:

What Joshu asks is, in some way, something that we all have on our minds. Yeah, I realize you don’t go around looking like Little Grasshopper asking monks what the ‘Way’ is. In fact, even if this idea might abide in some dark crevice of your mind, it is quite probable that you’ve never uttered this idea in the form of a direct question. What Joshu is asking is simply this: What is happiness? What is freedom? How can I live a happy life? Yes, I realize Joshu has phrased his question quite a bit differently but the words that are used depend on the values and notions of the culture they come from. In Joshu’s days, ‘Way’ was the meaning of the word ‘Tao’. Joshu was asking: What is the Tao? Some translations have Joshu ask: What is the Buddha? But it’s all the same thing. Joshu is asking for some specifications on what is the meaning of harmonizing with the Tao; what are the coordinates of our true nature (referred to as the Buddha Nature), what is the spontaneous healthy state of mind that brings around happiness and freedom.

Many people believe that happiness and freedom are things that we’re supposed to set out for, things that we have to acquire by doing stuff or changing our surroundings. Say, like having a bunch of money or being really famous. Others believe that these may be acquired by changing something within ourselves, like attaining certain states of mind. When ancient translations offer words like Buddha Mind or some other cryptic word for this situation, we seem to have a tendency to imagine super wacky states of mind. I used to think of the Buddha Mind as some detached, serene and all-knowing coolness. Wouldn’t it be great? Ah, all is falling apart and yet I’m just chill… Your round-the-corner-bookstore is bound to be packed with books that show you how to get to these ‘higher states of consciousness’ and propose methods and spiritual practices that serve as tickets to some ‘Prozac meets Xanax’ paradise.

But Nansen answers: ‘Hey, come down from the clouds! Stop imagining wacky stuff! Your ordinary mind, your stupid little confused mind is ALREADY IT. Anything else is just your imagination. Your little mind that thinks of koans that end with a PLOP is already the Tao. That is the Buddha Mind. Buddha Mind is not something special; it’s in fact quite ordinary.

But Joshu is no fool. I have this feeling that he knew exactly what Nansen was going to answer. He already knew about the ordinary mind and yet there were some things that didn’t quite fit. So following these lines, he shoots Nansen again: ‘How can it be studied (or developed)?’ That’s another thing that we have a tendency to do. We need to enhance, maintain or induce that which we believe to be good or desirable. If my ordinary mind is the Buddha Mind or the Tao then, what can I do to always have this mind? How can I keep it or make it even better? How can I follow this path to the ordinary mind?

But Nansen replies with words that are difficult to digest and truly hard to understand: ‘The more you pursue, the more does it slip away’. Your stupid, crappy little mind is already the Tao. Whatever you do to try to seize it, enhance it or improve it will just mess things up. It’s like stirring murky water to make it clear.

Many Zen teachers seem to have a standard answer for these things: ‘You just do zazen and it will all be settled.’ I find that a bit annoying. It’s like when you were a kid and someone would tell you: ‘You’ll understand it when you grow up’. However, and I am not a Zen Teacher mind you, I have to grant that while doing zazen all the stuff that’s going on in our minds becomes a bit more evident; it shows just a bit more clearly. In order not to sound like some pretentious Zen Master know-it-all, I’ll just share a bit of what happens to me. When I sit in zazen, the ordinary mind is there, flowing along in front of my attention. There are no obstructions. It just flows effortlessly and the usual parade of nonsense just goes by. Homer whacking Bart on the head… You know? The usual stuff. But then I get this itch, this anxiety to try and explain it, to try to control it or to change it. But the paradox is that when I try to seize it -to explain it- it’s like if I had to step out of my ‘mind’ to be able to rationalize it. It’s like moving away from the picture to see it in full scale. Anyway, when I do this, the flow is interrupted and the spontaneity is lost.

But our hero Joshu had already seen all this coming and had his third question ready and waiting. I imagine his reasoning was something like this: if my ordinary mind is already the Tao and there’s nothing I’m supposed to do to study it, then I just have to sit on my bum and do nothing! How can this be the Way? Isn’t this something like the Emperor’s New Clothes? What’s the difference then between just hanging around doing nothing and practicing the True Dharma preached the Buddhas of all times? If I just go about my business with my everyday state of mind, how can I be sure this is the True Way?

And this is when I should shut my big fat mouth.

Nansen’s reply is wonderful, concise and enlightening. How could I put my words on top of his? There’s an expression used in Zen teachings that goes something like: it would be like throwing buckets of water into the ocean. By trying to explain Nansen’s words, in fact, I would be throwing mud into the water to make it clear…

So let’s begin then. Here goes the first handful of mud…

Nansen replies Joshu by first tackling the issue of ‘knowing’ and ‘not knowing’. In this case, ‘knowing’ is meant as rational knowledge. How can I know it is the Way? What Joshu wants is some evidence, some convincing argument that holds its own water. He wants to be able to discuss this with his friends over dinner and tell them: ‘Hey, check this out: the Way is the Ordinary Mind. Breakthrough scientific research has proven that the limbic system is the blah, blah, blah.’ But these are just illusions. They are just more dopey thoughts parading in the sea of nonsense that goes on in our minds all the time. This discrimination is just a process of deconstructing experience into thought units (which we call ‘things’) and relate them thru a set of rules (which we call ‘logic’). But in the end, they are not reality; they are nothing but abstractions (Buddhism refers to these as ‘imaginations’.)

‘Not knowing’ is just the other side of the same coin. It is the things that we believe exist even if we are not aware of them or cannot explain them. It’s just the stuff that we are not discriminating, deconstructing and relating. How could this be relevant? It’s ‘outside the field of discrimination.’

And yet Nansen talks about getting to the path with no doubt. Blind faith, you might say… But it’s not quite that. Nansen means something more like intuition. The problem is that we have an idea of intuition that might be a bit different than what Nansen is talking about. We tend to believe that intuition is kinda like a hunch, like a funny feeling in the stomach. But we don’t usually think of intuition as something very precise or reliable. Anyway, Nansen’s intuition is more of a pre-verbal knowledge; something that we know of even if we haven’t yet put it into words. Getting to the Way without doubt is like recognizing your childhood neighborhood. It’s like looking someone in the eye and knowing that the words being uttered are honest. It’s like ducking when the blow approaches. You need no confirmation, no argument and no explanation. You know it before you ‘know it’; before you give it a name and discriminate it (understand it as something separate) from other stuff. OK?

Ah! But if you were Joshu you would have a fourth question welling up, wouldn’t you? What does all this have to do with happiness?

Even if Mumon gives a hint of this in his comment, at the same time he warns us: Nansen’s words could be dwelt upon for thirty years (a lifetime) before exhausting their meaning. Only then you’ll go PLOP. Won’t you?

No comments:

Post a Comment